|

Plans by

George Campbell.

1st rate 100 (3m). L/B/D: 226.5 × 52 × 21.5 dph (69m × 15.8m × 6.6m). Tons:

2,162 bm. Hull: wood. Comp.: 850. Arm.: 2 × 68pdr, 28 × 42pdr, 28 × 24pdr, 28

× 12pdr, 16 × 6pdr. Des.: Sir Thomas Slade. Built: Chatham Dockyard; 1765.

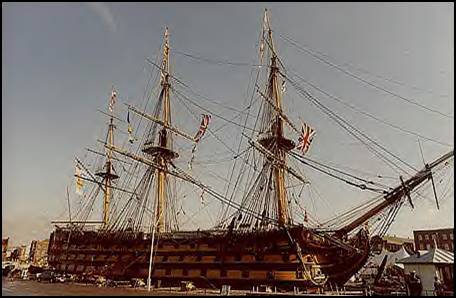

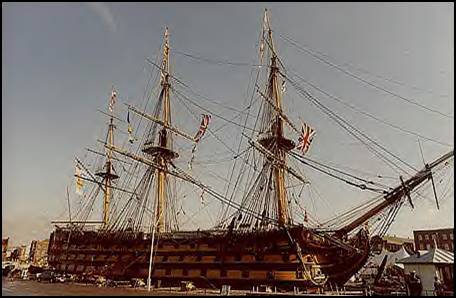

The seventh ship of the name and the third first-rate ship so called, HMS

Victory was launched in 1765, two years after the conclusion of the Seven

Years' War, but she was not commissioned until 1778. When France signed a

treaty of cooperation with the American colonies, Victory was made flagship

of Admiral Sir Augustus Keppel's Channel Fleet and, on July 23, took part in

an indecisive battle off Ushant (or Ile d'Ouessant, off the western tip of

Brittany), where she lost thirty-five killed and wounded. She remained in the

Channel Fleet for the next two years and was briefly assigned to Vice Admiral

Hyde Parker's North Sea convoy squadron designated to protect English

shipping from the Dutch, now allied with the French. On December 12, flying

the flag of Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, she captured a French convoy off

Ushant bound for America. In 1782, Victory was Lord Howe's flagship in the

relief of Gibraltar. Paid off at Portsmouth the following year, Victory

remained in ordinary for eight years.

In 1792, Victory became flagship of Vice Admiral Sir Samuel Hood's

Mediterranean Fleet, which occupied Toulon (surrendered to the English by

Loyalist troops) and captured Bastia and Calvi, Corsica, which Hood sought to

use as a British base in 1794.

The next

year, Admiral Sir John Jervis broke his flag in Victory. With only half as

many ships of the line as the French and Spanish combined fleets, Jervis

consolidated his force at Gibraltar. On February 14, 1797, he sailed with

fifteen British ships to intercept a large Spanish convoy guarded by

twenty-seven ships of the line. In the ensuing engagement off Cape St.

Vincent, the British broke the Spanish line and inflicted terrible damage on

the Spanish flagship, Principe de Asturias (112 guns) before forcing Salvador

del Mundo (112) to strike. Victory lost only nine killed and wounded in the

battle. The British also captured the first-rate San Josef and the

two-deckers San Nicolás and San Ysidro. Their success was due in no small

part to Admiral Lord Nelson, then in HMS Captain. In 1798 Victory returned to

Portsmouth, where she was considered fit only for a prison hospital ship at Chatham.

|

1/96

SCALE

6 -

SHEETS

SY-21

PRICE:

$ 55.00

In 1800 it was decided to rebuild Victory, a process that took three years.

On May 16, 1803, she became flagship of Lord Nelson's Mediterranean Fleet,

Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy commanding. At this time Napoleon had begun

formulating elaborate plans for the invasion of England, and Nelson was

ordered to contain Vice Admiral Pierre Villeneuve's squadron at Toulon. Flying his flag in Bucentaure, Villeneuve slipped out in January 1805, returned,

and sailed again on March 30. After picking up Admiral Federico Carlos

Gravina's Spanish fleet at Cadiz, Villeneuve sailed for a rendezvous with

other French forces at Martinique. Learning of his move, Nelson set off in

hot pursuit across the Atlantic. In June, Villeneuve learned that Nelson had

followed him, and he returned to Europe almost immediately. Nelson followed

close behind, arriving off southern Spain four days before the Combined Fleet

skirmished with Admiral Sir Robert Calder's fleet off El Ferrol.

Villeneuve arrived at Cadiz on August 21, and remained there, blockaded first

by Vice Admiral Sir Cuthbert Collingwood and then, in October, by Nelson,

fresh from meetings in London with Prime Minister William Pitt and First Lord

of the Admiralty Lord Barham. Daunted by the prospect of an engagement with

the British fleet, Villeneuve stayed put until he learned that Napoleon was

relieving him of his command. At 0600 on October 19, the Combined

Fleet—eighteen French and fifteen Spanish ships of the line—weighed anchor,

and within two and a half hours, the news had been signaled to Nelson, fifty

miles to the southwest. The fleet took two days to straggle out of Cadiz, and at first it seemed as though Villeneuve was going to make a run for the Mediterranean. But at 0800 on October 21, he turned back to face Nelson. Twelve days

before, Nelson had outlined his plan of attack, "the Nelson Touch,"

as he called it in a letter to Emma Hamilton:

The whole impression of the British Fleet must be to overpower from two or

three ships ahead of their Commander-in-Chief, supposed to be in the Centre,

to the Rear of their Fleet.... I look with confidence to a Victory before the

Van of the Enemy could succour their Rear.

On the eve of the battle, he concluded his remarks to his officers with the

encouraging observation, "No Captain can do very wrong if he places his

ship alongside that of an enemy."

In a move that might well have failed under any other commander, Nelson

divided his fleet into two divisions, the weather division headed by Victory

and the lee by Collingwood in HMS Royal Sovereign. As the British lines

approached the Combined Fleet, at 1125 Nelson ordered his most famous signal

run up Victory's masts: "England expects that every man will do his

duty." Victory failed to cut off Bucentaure, but she came under all but

unchallenged broadsides from Redoutable for forty-five minutes. Finally, at

1230, Victory let off a broadside into the stern gallery of the French

flagship, though she was soon enfiladed by Bucentaure, Redoutable, under

Jean-Jacques Lucas, and the French Neptune. (The Roman sea god was impartial

at Trafalgar, which also saw the participation of HMS Neptune and the Spanish

Neptuno.) Nelson had insisted on wearing his full allotment of medals and

decorations, and at 1325 he was wounded by a French sharpshooter as he paced

the quarterdeck with Hardy. In the meantime, Redoutable and Victory lay side

by side, exchanging murderous volleys until Redoutable drifted into HMS

Téméraire. Stuck fast between the unrelenting broadsides of the two British

ships, Redoutable finally surrendered and Victory was out of the battle by 1430.

Her mizzen topmast was shot away, many of the other masts severely weakened,

and her bulwarks and hull considerably shot up. Nelson had been taken below,

and at 1630—having first been informed of the capture of fifteen of the enemy

ships—the hero of Copenhagen, the Nile, and now Trafalgar, died.

British prizes numbered more than nine French and ten Spanish ships,

including Bucentaure. Of these, two escaped, four were scuttled, and eight

sank in a storm that hit after the battle. Casualties in the Combined Fleet

totaled 6,953, as against 448 British dead and 1,241 wounded; Victory lost 57

dead and 102 wounded. Towed to Gibraltar by HMS Neptune, Victory sailed for England, reaching Sheerness on December 22, from where Nelson's body was carried to St. Paul's Cathedral for a state funeral. His death was not in vain, for with Trafalgar he

had destroyed the French and any threat of a Napoleonic invasion of Britain. England would rule the seas uncontested for a century. Defeated at sea he may have

been, but six weeks later Napoleon's armies won a crushing victory at Austerlitz, and Napoleon would try the fate of Europe for another decade.

After a refit at Chatham, in 1808 Victory reentered service as the flagship

of Sir James Saumarez's Baltic Fleet, which blockaded the Russian fleet and

kept open the supply of naval stores from Sweden. Except for a brief spell

escorting a troop convoy for the relief of the Duke of Wellington's forces in

the Peninsular Campaign, she remained in the Baltic until paid off in 1812. Since

1824, Victory has served as flagship of the commander in chief at Portsmouth. In 1922 she was dry-docked and opened as a museum. She received her last battle

wound in World War II, when a German bomb exploded in her dry-dock.

Reference: Bennett, Nelson the Commander. Bugler, HMS Victory. Fraser, H.M.S.

Victory. Longridge, Anatomy of Nelson's Ships. McKay, 100-gun Ship Victory.

Mackenzie, Trafalgar Roll. Schom, Trafalgar.

Hull Length 27.5 inches.

|